Evaluation of biosecurity at large-scale commercial pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam

Phan Thi Duy Thuan 1 Duong Thanh Hai 1 Vu Thi Minh Phuong 1

- Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Hue University of Agriculture and Forestry, Hue, Vietnam

Article Information

- Date Received: 23/12/2025

- Date Revised: 03/01/2026

- Date Accepted: 04/01/2026

- Date Published Online: 05/01/2026

Copyright: © 2025 The Authors. Published by MARCIAS AUSTRALIA, 32 Champion Drive, Rosslea, Queensland 4812, Australia. This is an open access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Citation: Thuan PTD, Hai DT, Phuong VTM (2025). Evaluation of biosecurity at large-scale commercial pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam. Aust J Agric Vet Anim Sci (AJAVAS), 1(3), 100004

https://doi.org/10.64902/ajavas.2025.100004

Abstract

African swine fever (ASF) continues to pose a major threat to pig production in Vietnam, highlighting the critical role of farm-level biosecurity. This study aimed to evaluate the biosecurity status of large-scale commercial pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam using a standardised digital assessment tool. A cross-sectional survey was conducted on five commercial pig farms (≥300 livestock units) using the Food & Agriculture Organisation’s framework based PigHealth Security-X software, which comprises 165 questions grouped into eight biosecurity vectors. Biosecurity performance was quantified on a scale from 0 to 100%. Overall, all surveyed farms were classified as having an excellent level of biosecurity, with a mean score of 91.3%. Nevertheless, three vectors showed comparatively lower scores: Good husbandry practices (83.4%), transportation (85.0%), and structural location (85.6%). Major non-compliant indicators included high stocking density, frequent entry of external vehicles, insufficient vehicle disinfection time, and the absence of off-site disinfection facilities. These findings indicated that despite high overall biosecurity scores, specific operational weaknesses that may increase the risk of pathogen introduction and spread remained. Regular biosecurity assessments using digital tools such as PigHealth Security-X can support farm managers in identifying critical control points and implementing targeted improvements to strengthen disease prevention and control in commercial pig production systems.

Keywords:

Biosecurity, pig fattening, commercial large scale pig farms, PigHealth Security-X

Highlights

- The study used PigHealthy-Security X software to assess the biosecurity level of large-scale pig fattening farms;

- Large-scale pig fattening farms in Central Viet Nam achieved an excellent level of biosecurity, with a score of 91.3%;

- Good husbandry practices, transportation and farm structural location are key vectors needed to improve biosecurity level

1.0 Introduction

Pig production is a major cornerstone of the livestock sector in Vietnam; contributing more than 60% of the total domestic meat output and playing a critical role in food security and rural livelihoods. Over the past decade, the sector has undergone rapid intensification, with a marked increase in large-scale commercial pig farms. While intensification improves productivity and efficiency, it also elevates the risk of infectious disease transmission, particularly transboundary animal diseases such as African Swine Fever (ASF). Since its introduction into Vietnam in 2019, ASF has caused severe economic losses, mass culling of pigs, and long-term disruptions to the pig industry. The disease remains endemic in many regions, including Central Vietnam, due to continuous circulation of the virus and frequent movements of animals, vehicles, and personnel within complex production networks (Chenais et al., 2019; WOAH, 2023). In the absence of a fully effective and widely available commercial vaccine, biosecurity remains the most effective and sustainable strategy for preventing the introduction and spread of ASF virus at the farm level (FAO, 2010).

The United Nations’ Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) defines biosecurity in pig farming as the implementation of a comprehensive set of management, physical, and operational measures designed to reduce the risk of pathogen introduction, establishment, and dissemination within and between farms (FAO, 2010). Numerous studies have demonstrated that improved biosecurity is associated with reduced disease incidence, enhanced herd health, and improved production performance (Postma et al., 2016; Alawneh et al., 2014). However, biosecurity is a multifaceted concept, encompassing internal measures (e.g., animal management, hygiene, personnel practices) as well as external measures (e.g., farm location, transportation, and control of farm access).

Previous studies in Vietnam largely focussed on biosecurity practices in smallholder household pig farms, where compliance levels are often low to moderate due to limited resources and lack of standardised management systems (Ngan et al., 2016; Tuan et al., 2021). In contrast, empirical evidence on the biosecurity status of large-scale commercial pig farms remains limited, particularly in Central Vietnam, a region characterised by diverse production systems, high farm density in certain areas, and frequent animal movements. Moreover, conventional biosecurity assessments are often qualitative, time-consuming, and subject to evaluator bias, limiting their comparability across farms and regions. In recent years, digital assessment tools have been developed to address these limitations by providing standardised, quantitative, and user-friendly approaches to evaluating farm biosecurity. The PigHealth Security-X software is one such tool, designed to assess biosecurity performance across multiple vectors using a structured set of indicators to generate numerical scores that facilitate comparison and monitoring over time (Tuyen et al., 2021). Despite its potential advantages, empirical applications of this tool in large-scale commercial pig farms are still scarce.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the biosecurity status of selected large-scale commercial pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam using the PigHealth Security-X digital assessment tool and to identify critical biosecurity gaps requiring targeted corrective measures. The findings are expected to contribute to improving biosecurity management, supporting evidence-based decision-making, and strengthening disease prevention strategies in intensive pig production systems under high ASF risk conditions.

2.0 Materials and methods

2.1. Study farms and size

The survey was conducted at five large-scale commercial pig-fattening farms (≥300 livestock units in accordance with subsisting 2018 Vietnamese Livestock Law operational in the Central Region) within the same season and year.

2.2. Survey and assessment methods

The survey and assessments were performed using the PigHealth Security-X software. Biosecurity assessment scores ranged from 0% to 100%. The PigHealth Security-X software was developed by Tuyen et al., (2021) at the Faculty of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine, Ho Chi Minh City University of Agriculture and Forestry. The application runs on iOS and Android operating systems. The programming language used for the smartphone application is Dart, and it utilises Flutter as a framework (a set of pre-written code snippets that form a framework and packaged programming libraries). The software link is: https://apps.apple.com/vn/app/pighealth-security-x/id1584189321

2.3. Survey indicators

The traditional biosecurity assessment model comprises 165 questions grouped into eight vectors: structural location (46 questions), good husbandry practices (43 questions), management (13 questions), transportation (12 questions), equipment and materials (22 questions), vermin and bird control (6 questions), feed and water (10 questions), and personnel (13 questions) (Doanh et al., 2022).

2.4. Data analysis

The data were processed and statistically analysed to calculate percentage and mean values. Since the data were collected on farms with similar animal numbers, within the same season and year, a simple one-way analysis of variance fitting the fixed effect of farm was utilised and significant differences between farms at the p<0.05 level were separated using DMRT. Due to the small sample size, only descriptive statistics of the biosecurity scores were reported.

3.0 Results

3.1. Biosecurity level

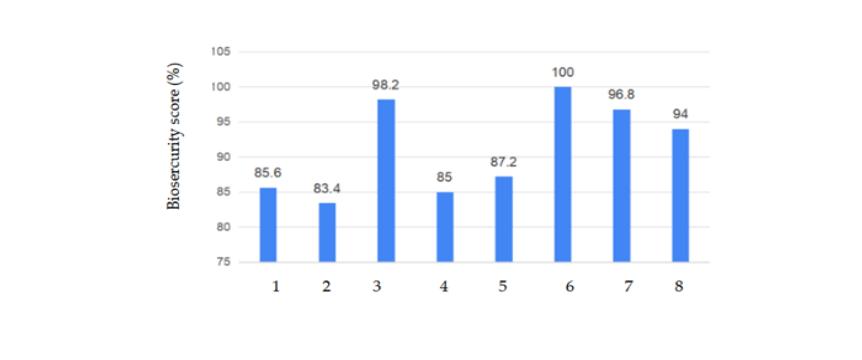

The biosecurity assessment of the five large-scale commercial pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam revealed a consistently high level of compliance with recommended biosecurity standards. The mean overall biosecurity score was 91.3%, classifying all surveyed farms as having an excellent biosecurity level according to the PigHealth Security-X scoring system. Biosecurity scores varied among the eight assessed vectors (Figure 1). The vectors related to internal farm management, including management (98.2%), feed and water (96.8%), vermin and bird control (100%), and personnel (94.0%), achieved the highest scores. In contrast, comparatively lower biosecurity scores were recorded for good husbandry practices (83.4%), transportation (85.0%), and structural location (85.6%). These vectors are primarily associated with external biosecurity and interfaces between the farm and its surrounding environment.

Figure 1. Biosecurity scores of vectors for large-scale pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam, where 1.Structural location, 2. Good husbandry practices, 3. Management, 4. Transportation, 5. Equipment and materials, 6.Vermin and bird control, 7. Feed and water, 8. Personnel.

3.2. Assessment criteria not met and corrective measures for large-scale pig farms in Central Vietnam.

3.2.1 Structural Location Vector

This vector plays a very important role in biosecurity measures. However, surveys show that farms in Central Vietnam still had many limitations, especially disinfection as portrayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Criteria of the bio safety of Structural Location vector that did not meet the expected standards.

| Criteria | Number of Farms | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The farm did not have an external disinfection facility (located more than 1km away) for vehicles to use once before entering the camp area. |

3 / 5 | 60% |

| The disinfection facility did not use hot water (>60°C) to spray and wash the car. |

3 / 5 | 60% |

| The farm grew trees and vegetables and also raised fish in a pond. | 3 / 5 | 60% |

3.2.2 Good Husbandry Practices vector

The Good Husbandry Practices vector recorded the lowest biosecurity score among the eight surveyed vectors, at 83.4%.

Table 2. Biosafety criteria of Good Husbandry Practices vector that did not meet the expected standards.

| Criteria | Number of Farms | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The farm imported fattening pigs and breeding pigs from outside. | 5 / 5 | 100% |

| Pig stocking density in each pen of the farm. | 5 / 5 | 100% |

3.2.3 Management vector

Although with regards to the management vector, most farms achieved a very high biosecurity score of 98.2%, but some of the farms still failed to meet the standard because they lacked regulations prohibiting “pig caretakers from moving between different areas or rows of pens.” Therefore, all farms need to strictly enforce this regulation to avoid cross-contamination between areas.

3.2.4 Transport vector

The transport vector’s success rate is 85%, lower than other vectors. The limitations faced by the farms are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Biosafety criteria of Transport vector that did not meet the expected standards.

| Criteria | Number of Farms | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of vehicles from outside (feed trucks, pig purchasing trucks, equipment, repair and maintenance trucks, etc.) entering the farm. | 4 / 5 | 80% |

| Time for soaking and spraying the vehicle with chemicals. | 5 / 5 | 100% |

3.2.5 Equipment and materials vector

The vector of equipment and materials in the Central Region farms achieved an overall biosecurity score of 87.2% (Table 4).

Table 4. Biosafety criteria of Equipment and materials vector that did not meet the expected standards.

| Criteria | No. of Farms | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Personal items (laptops, phones, watches, rings, etc.) that must be brought to the farm | 4 / 5 | 80% |

| The farm exchanged livestock equipment with other farms or shared equipment between different barn rows | 3 / 5 | 60% |

3.2.6 Food and water vector

The food and water vector of the farms in Central Vietnam had very high biosecurity scores (96.8%). However, one farm still did not regularly clean and disinfect the silo system and feed delivery pipes. This led to the risk of disease outbreaks and spread within the farm.

3.2.7 Personnel vector

The biosafety score of this human vector at the Central Vietnam camps was excellent at 94%. The indicators that were not met in the Central Vietnam farms were the quarantine period for people entering the farm and the use of protective equipment when entering the livestock area. However, only 1-2 farms had this issue.

4.0. Discussion

The high overall biosecurity score observed in this study reflects the increasing adoption of stringent biosecurity measures in large-scale commercial pig farms in Central Vietnam. This trend likely results from heightened awareness of ASF risks, and the substantial economic losses associated with disease outbreaks. Comparable findings have been reported in commercial pig farming systems in the Philippines, where large farms demonstrated higher biosecurity compliance than smallholder operations (Alawneh et al., 2014). Despite the excellent overall performance, weaknesses were consistently identified in vectors related to external biosecurity.

Structural location deficiencies, including the lack of off-site disinfection facilities, and limited separation between production areas and surrounding activities, further increase the risk of pathogen introduction. Farm location and layout have been identified as critical determinants of external biosecurity effectiveness, particularly in regions with high pig densities and complex production networks (WOAH, 2023). To improve the level of biosecurity at the Structural location vector level, the following corrective measures should be implemented: An additional washing area should be designated outside the farm for a first wash; washing equipment must be fully equipped and in good working order. Farms need to use hot water (>60°C) for washing because it has a dual effect of limiting the possibility of pathogen survival and spread. Furthermore, farms using fertilizers specifically designed for crops and pig manure from the farm, must safely treat using biogas, settling tanks, or composting methods to produce organic fertilizer before application.

Good husbandry practices: High stocking density and the introduction of pigs from external sources represent significant risk factors for disease introduction and amplification. Overstocking has been shown to facilitate rapid pathogen spread once biosecurity barriers are breached, especially in confined housing systems (Maes et al., 2020; Postma et al., 2016). The key issues that need to be addressed to improve biosecurity at the Good husbandry practices vector level include: Establishing a program for controlling the source of in-coming pigs, ensuring the quality of breeding stock, and implementing proper quarantine and acclimatisation procedures. The quarantine period for newly introduced pigs should be sufficiently long (56–90 days) to eliminate latent infections, allow pigs to adapt to farm conditions, and develop immunity through vaccination programs. Maintaining appropriate stocking densities according to age, body weight, and growth rate to minimise stress and facilitate proper animal care will enhance biosecurity.

It was also apparent that the practice of biosecurity compliance at the Management vector level on large farms was much better than on smaller farms. This finding aligns with previous reports indicating that in-house farms had a score of 69.7% without restricting outside visitors (Ngan et al., 2016), and if they did not implement the “all in – all out” rule (Tuan et al., 2021).

Transportation emerged as a major vulnerability factor, consistent with previous reports identifying vehicles as one of the most important mechanical vectors for ASFV transmission between farms (FAO, 2010; Chenais et al., 2019). Insufficient disinfection time and frequent vehicle entries increase the likelihood of virus survival and mechanical transfer. Studies in Vietnam have similarly highlighted inadequate vehicle biosecurity as a persistent challenge, even in relatively well-managed farms (Ngan et al., 2016; Tuan et al., 2021). This research finding is also similar to a previous report by Vi et al., (2016) that studied 110 livestock farms in the Southeast Region of Vietnam and found that the rate of farms disinfecting vehicles entering and exiting the farm was 53.6%. The corrective measures are as follows: Scheduling entry and exit activities to minimise the number of movements per week, and separating clean and dirty transport categories by specific time intervals to effectively eliminate biosecurity risks. Vehicles must be cleaned, disinfected, and allowed to dry completely at the gate or outside the farm premises. Disinfection time should be regulated based on the concentration and type of disinfectant used. Trucks should remain empty for a sufficient period, and a designated driving route should be established, located as far away from the animal housing area as possible. Ideally, transport vehicles and workers responsible for loading and unloading pigs should operate in a fixed location with a designated pathway, ensuring a safe distance from the production area.

Problems persist regarding equipment and supplies vector: Personal items brought to the farm posed a significant risk of disease transmission. Therefore, bringing personal items into the farm should be restricted, and if brought in, they must be cleaned, disinfected, and isolated for a specified period. Farms still shared equipment, with the possible risk of infection between rows of pens. Therefore, when moving between pens, all equipment should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Our current research findings are consistent with those of Tuan et al., (2016) who reported a biosecurity score of 84.82% in a survey of 112 farming households that shared equipment between pens, thus posing a significant risk for disease outbreaks. Remedial measures include: The prohibition of personal supplies being brought to the farm. If permitted, such supplies must be fully disinfected and isolated in strict compliance and adherence to standard biosecurity procedures. If equipment is shared between different rows of pens, it must be rigorously disinfected.

In food and water vector, the farms performed better than the households (Tuan et al., 2021). However, cleaning the silo systems needs to be thorough and regular on farms. To overcome some of the limitations of personnel vector, farms in Central Vietnam need to stipulate a minimum quarantine period of > 2 days to limit the retention of pathogens in humans. Strict regulations and penalties should be applied to workers and farmers who do not fully comply with wearing protective equipment and disinfection when entering production areas.

The findings of this study emphasise that a high overall biosecurity score does not necessarily equate to negligible disease risk. Instead, targeted improvements focusing on specific weak vectors are essential. Regular, standardised biosecurity assessments using digital tools such as PigHealth Security-X can support continuous monitoring and evidence-based management decisions. Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of our study: The small sample size restricts extrapolation to all large-scale pig farms in Central Vietnam, and partial reliance on self-reported data may introduce reporting bias. Nevertheless, the use of a structured and validated assessment tool enhances the robustness and comparability of the findings.

Conclusion

The study found that large-scale pig fattening farms in Central Vietnam achieved an excellent level of biosecurity (91.3%). The vectors needing improvement to ensure top-notch biosecurity levels are: Good husbandry practices, transportation, and structural location. Measures to improve biosecurity levels include: (i) Ensuring effective disinfection of transportation vehicles, equipment, supplies, and workers involved in farming, and (ii) Ensuring appropriate pig stocking density in each pen.

Recommendations:

Farms should use the PigHealthy-Security X software to periodically assess biosecurity scores to ensure improved biosecurity within the farm. They should strictly comply with, and fully implement biosecurity measures.

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai Methodology: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai ; Software: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai; Validation: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai, Vu Thi Minh Phuong ; Formal analysis: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai; Investigation: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai, Vu Thi Minh Phuong; Resources: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai; Data Curation: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai, Vu Thi Minh Phuong; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai; Writing—Review and Editing: Phan Thi Duy Thuan, Duong Thanh Hai. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Ethics Approval Statement: This was a survey only and did not involve animal experimentation, hence institutional animal ethics approval was not needed.

Data Availability Statement: All the relevant data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge the support of the scientific research project from the University of Agriculture and Forestry, Hue University, code DHNL 2024 -CNTY 06.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Artificial Intelligence: AI was not used for this original research article.

References

Alawneh JI, Barnes TS, Parke C, Lapuz E, David E, Basinang V, Baluyut A, Villar E, Lopez EL, Blackall PJ. 2014. Description of the pig production systems, biosecurity practices and herd health providers in two provinces with high swine density in the Philippines. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 114(2), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.01.020

African Swine Fever: The better the biosecurity measures, the lower the risk of the disease. https://nhachannuoi.vn/benh-dich-ta-heo-chau-phi-lam-tot-an-toan-sinh-hoc-den-dau-rui-ro-benh-cang-thap-toi-do/

Chenais E, Depner K, Guberti V, Dietze K, Viltrop A, Stahl K. 2019. Epidemiological considerations on African swine fever in Europe 2014–2018. Porcine Health Management, 5, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-018-0109-2

Doanh NH, Tuyen LTT, Van LN, Nho LTH, Phuc NT, Hue VT, Phong DD, Duy DT. 2022. PigHealth Security-X: Application of new biosecurity in pig farming towards biosecurity and sustainability. https://nhachannuoi.vn/pighealth-security-x-ung-dung-an-toan-sinh-hoc-moi-trong-chan-nuoi-heo-theo-huong-an-toan-va-ben-vung/

FAO OIE – World Organisation for Animal Health. 2010. Good practices for biosecurity in the pig sector: Issues and options in developing and transition countries, Repr. 2010 (July), FAO Animal Production and Health Paper 169. Rome. https://www.fao.org/4/i1435e/i1435e00.htm

Maes D, Sibila M, Kuhnert P, Segalés J, Haesebrouck F, Pieters M. 2020. Update on Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infections in pigs: Knowledge gaps for improved disease control. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 67(3), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13448

Ngan PH, Nhiem DV, Tra VTT, Ha NM, Nam DP, Unger Fred (2016). Applying biosecurity at pig farms in Hung Yen and Nghe An. Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology, 28(1), 79-84. https://vjol.info.vn/index.php/kk-ty/article/view/35930

Postma M, Backhans A, Collineau L, Loesken S, Sjölund M, Belloc C, Dewulf J. 2016. The biosecurity status and its associations with production and management characteristics in farrow-to-finish pig herds. Animal, 10(3), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731115002487

Tuan HM, Cuc NTK, Dinh NC, Thong TT, Trung NV, Son PV, Ninh PH, Tuyen NT, Thanh TK, Son NN. 2021. Assessment of the current state of biosecurity in pig farming households in Vietnam. Journal of Science and Animal Husbandry, 124, 71-84. https://tapchivcn.vn/khcn/article/view/337

Tuyen LTT, Doanh NH, Van LN, Phuc NT, Hue VT, Phong DD, Duy DT. 2021. Biosecurity innovation in the era of African swine fever. https://nhachannuoi.vn/doi-moi-an-toan-sinh-hoc-trong-ky-nguyen-dich-ta-heo-chau-phi/

Vi TQ, Hien LT, Hoa HTK. 2016. Assessing the level of biosecurity at some pig farms in the Southeast region. Journal of Livestock, 210, 82-90. https://scholar.dlu.edu.vn/thuvienso/handle/DLU123456789/255426

WOAH (World Organisation for Animal Health). 2023. African swine fever (ASF): Prevention and control. Paris, France. https://www.woah.org/en/disease/african-swine-fever/

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, institutional affiliations, data contained in all publications, and all responsibilities for accuracy are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MARCIAS AUSTRALIA and AJAVAS/or the Editor(s). MARCIAS AUSTRALIA and AJAVAS/or the Editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.