Economic impact of animal diseases in Nigeria: A systematic review

Abubakar Y Hassan 1 Aliyu Abdulkadir 1 Ammar U Bashir 2 Ishaq Ibrahim 3 Kabir M Moyi 4 Bilkisu A Ibrahim 1 Muhammed S Isah 1 Maryam Nasiru 1 Yero I Hassan 1

- Department of Veterinary Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

- National Animal Production Research Institute, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria

- Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries Development, Sokoto, Nigeria

- Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Article Information

- Date Received: 07/10/2025

- Date Revised: 16/12/2025

- Date Accepted: 18/12/2025

- Date Published Online: 24/12/2025

Copyright: © 2025 The Authors. Published by MARCIAS AUSTRALIA, 32 Champion Drive, Rosslea, Queensland, Australia. This is an open access publication under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Citation: Hassan AY, Abdulkadir A, Bashir AU, Ibrahim I, Moyi KM, Ibrahim BA, Isah MS, Nasiru M, Hassan YI (2025). Economic impact of animal diseases in Nigeria: A systematic review. Aust J Agric Vet Anim Sci (AJAVAS), 1(2), 100006

https://doi.org/10.64902/ajavas.2025.100006

Abstract

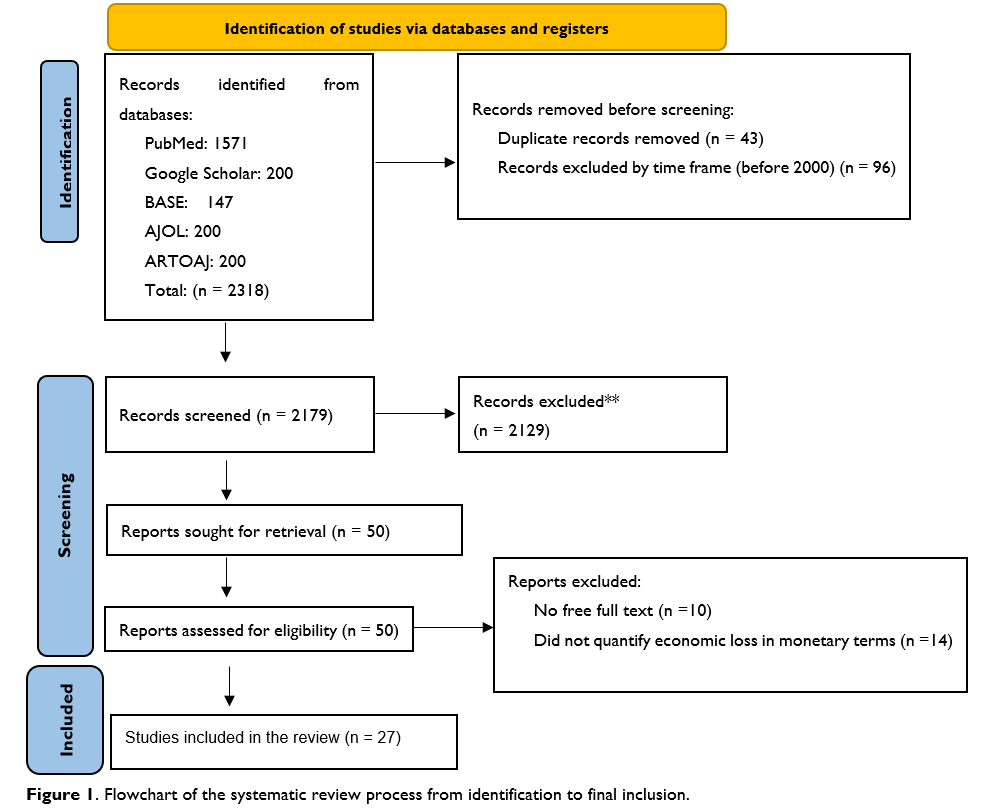

Evaluating the distribution of animal disease burden across the value chain and its impact on the economy informs relevant policy development and facilitates targeted investment in sustainable livestock production. The Nigerian agricultural sector contributes about 24% to the GDP and employs 34% of the national workforce. However, animal diseases threaten this sector due to weak veterinary infrastructure, fragmented vaccination campaigns, inconsistent surveillance, and reactive responses to disease outbreaks. Whilst the threats of animal diseases to the profitability and sustainability of the livestock sector is worldwide, in Nigeria, these threats emanate from both the negative economic impacts and weak preventive measures taken to minimise the introduction or spread of animal diseases. Designing a robust national control plan remains limited due to the lack of systemic and locally contextualised evidence. This review aimed to access, retrieve, critically synthesise, and assess scattered reports of animal diseases in Nigeria to provide a comprehensive information that is essential for the development of relevant evidence-based disease control policies. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, BASE, AJOL, and ARTOAJ databases to identify relevant publications from 2000-2025 based on data availability. Articles were included if they clearly quantified economic losses from animal diseases in Nigeria. Articles were excluded if they were not in English, not focused on Nigeria, or if the full text was unavailable. A total of 2318 articles were screened, 50 were sought for retrieval and 27 were included in the review. Losses ranged from USD 15.87 (5,005.85 Nigerian Naira) to USD 456,905,311.00 (700,304,123,857.00 Nigerian Naira). The review also highlights the need for the use of economic models to capture invisible losses across the value chain, providing further insight into the impact of livestock diseases in Nigeria.

Keywords:

Animal diseases, economic impact, livestock, agriculture, Nigeria

Highlights

- Nigeria loses billions of dollars to animal diseases

- Weak animal disease control policies and difficult implementation plans plague the livestock sector

- Invisible cost is under-reported.

1.0 Introduction

Global significance of livestock and animal diseases: Animal diseases threaten the global livestock sector in terms of economic impacts (Bose and Kumar, 2025). As zoonotic diseases of animal origin have a substantial impact on human health and agricultural productivity, the measures taken to minimise the risk of disease introduction or spread are crucial (Rich and Perry, 2011). However, investigating the economic impacts of animal diseases is complex due to the unique features of each disease in diverse species and distinct mechanisms of spread (Countryman et al., 2024). In most parts of the developing world, livestock play a crucial role in household livelihoods and serve as a pathway out of poverty (Rich and Perry, 2011). In many low and middle-income developing countries, the agricultural sector continues to be the largest contributor of food, inputs, employment opportunities, industrial raw materials, foreign exchange earnings from the exportation of surpluses, and substantial value-addition to various production processes (Sertoğlu et al., 2017).

The livestock sector in Nigeria and its challenges: The agricultural sector is considered as one of the primary drivers of growth and development (Sertoğlu et al., 2017) and pivotal to achieving Nigeria’s food security (Bolajoko et al., 2021). The agricultural sector contributed 24% of Nigeria’s 2024 GDP (National Bureau of Statistics, 2024) and employed 34% of the country’s workforce (National Bureau of Statistics, 2025). Furthermore, the livestock sub-sector contributed USD 32 billion to Nigeria’s GDP (Natsa, 2025). Nigeria has one of the largest livestock populations in Africa, wherein approximately 70% of the sheep and goats are spread around northern Nigeria (Rawlins et al., 2022). However, animal diseases threaten the country’s livestock sector (Alhaji et al., 2020; Sadiq and Mohammed, 2017). For instance, disease outbreaks in poultry alone severely impacted the resilience of 20 million Nigerian poultry farmers (Sowunmi, 2025).

Existing gaps in knowledge and policy integration: In Nigeria, despite the availability of some animal disease burden estimates, the integration of such available evidence in designing a robust national control plan remains limited. This is demonstrated by weak veterinary infrastructure, fragmented vaccination campaigns, inconsistent surveillance, and reactive rather than proactive responses to disease outbreaks. Moreover, the Nigerian Livestock Roadmap (FAO, 2020) highlights the urgent need to “remodel the financial and economic costs of animal disease burden” to inform structured policy interventions and investment actions. Additionally, available evidence shows that policy effectiveness in Nigeria is often met with setbacks owing to the lack of systemic, locally contextualized evidence. Furthermore, due to the complexity of the livestock value chain, economic analysis of animal diseases remains fragmented, often only covering individual diseases or production systems without integrating across the entire livestock sector value chain (Kappes et al., 2023).

Purpose and objectives of the review: In the light of this contextual framework, this comprehensive systematic review aiming to identify the economic impacts of animal diseases in Nigeria is timely and needed. Such a review has the primary objective of synthesising fragmented evidence, identifying high-impact diseases, exposing gaps in knowledge, and offering robust guidance for prioritising control interventions. The review also aims to provide a sound scientific foundation and data-driven strategy that policymakers and veterinary authorities need to advance evidence-based disease control programs.

2.0 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and protocol registration: This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines according to Tawfik et al., (2019), with the main adaptation being a sole reviewer was responsible for screening and assessing identified articles during the electronic database search. Limited risk-of-bias analysis was conducted. These guidelines were selected due to their focus on policy decision-making. 2.2 Search strategy: The Systematic literature search was conducted in August 2025 on PubMed, Google Scholar, BASE, AJOL, and ARTOAJ databases to identify relevant publications from 2000-2025. This date range was chosen based on data availability. The search was last conducted in October 2025. Furthermore, the search utilized a combination of keywords, including: (Animal diseases OR Veterinary diseases OR Livestock diseases OR Animal Production diseases) AND (Economic impact OR Economic significance OR Economic importance) AND (Nigeria). Due to the volume of records retrieved from Google Scholar, AJOL, and ARTOAJ search, only the first 200 results from the three databases were screened to capture as many relevant articles as possible, whilst balancing the resource-intensive extraction. All results from PubMed and BASE were included in the screening process. Duplicates were removed manually before screening titles and abstracts for relevance.

2.3 Eligibility criteria: Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were considered for inclusion. Studies were excluded during the title screening if they addressed human diseases, pertained to countries other than Nigeria, or did not explicitly reference Nigeria. Additionally, articles were excluded if they were exclusively experimental studies, systematic reviews, or did not report on viral, bacterial, or parasitic diseases. During abstract screening, studies meeting any of these exclusion criteria were also removed. For titles lacking clear information or involving animal diseases without explicit economic impact assessments, the full text was retrieved and reviewed. Articles without electronically accessible abstracts or full texts were excluded if their title or abstract did not explicitly mention any animal disease, economic impact, or assessment. Furthermore, review articles were identified, and their reference lists were scrutinized to locate additional relevant papers, which were then screened according to the same inclusion and exclusion criteria described.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the systematic review process from identification to final inclusion.

Following the elimination of duplicates and the initial screening, 47 documents were selected for further examination. Due to the unavailability of full texts, 10 documents were excluded from the study. Furthermore, 13 articles did not quantify economic losses in monetary value and were therefore eliminated. Post revision, 2 articles were added, resulting in a total of 27 articles being selected for the study. Economic impact was defined as financial loss incurred from morbidity, mortality, reduced productivity, and carcass or offal or organ condemnation because of animal disease(s) in Nigeria. Subsequently, full articles were read, and studies were included if they applied a quantitative economic impact assessment of animal diseases in Nigeria.

3.0 Results

The review is summarised in 4 Tables to provide a clearer understanding of the economic impact of animal diseases in Nigeria. Table 1 provides an overview of included studies with key economic findings, Table 2 summarises the economic impact of viral diseases, Table 3 summarizes economic impact of bacterial diseases and finally Table 4 summarizes the economic impact of parasitic diseases. These tables serve as a framework for the detailed economic impact analysis.

Table 1: An overview of included studies with key economic findings

| Author | Year | Geopolitical zone | Study type | Sample size | Key findings |

| Dauda et al. | 2025 | North-Central | Cross sectional | 5,779 | *Economic loss from condemned organs USD 21,048 (19,995,600 Nigerian Naira) |

| Blake et al. | 2020 | Did not specify | Williams model | NA | EUR 58,670,000 (USD 78,905,283.59) (120,872,712,522.09 Nigerian Naira). The highest cost of coccidiosis in sub-Saharan Africa |

| Rawlings et al. | 2022 | Did not specify | Integrated stochastic prod and economic herd models | 300 herds | EUR 24,000,000 (USD 27,952,488) (49,361,568,000.00 Nigerian Naira) sheep and goat pox cost |

| Njoga et al. | 2023 | South-East | Cross sectional | 1452 cattle, 1006 pigs and 924 goat carcasses | 391,089.2 kg of diseased meat/organs valued at USD 235,030 (978,000,000 Nigerian Naira) were condemned. |

| Sanni et al. | 2023 | Did not Specify | Modelling | 43,662,085 cases | Poultry loss USD 456,905,311 (700,304,123,857.00 Nigerian Naira) |

| Limon et al. | 2020 | North-East | Retrospective | 165 farmers | Overall economic impact was USD 6,340.00 (9,697,093.40 Nigerian Naira) |

| Ola-Fadunsin et al. | 2020 | North-Central | Retrospective | 832,001 cattle slaughtered | Disease associated loss was USD 304,133.82 (46,161,433 Nigerian Naira) |

| Alhaji et al. | 2020 | North-Central | Cross sectional | 660 herds | Economic impact of FMD was USD 16,055,368.00 (24,548,818,225.68 Nigerian Naira) |

| Odeniran et al. | 2020 | Did not specify | Economic model | 2.1 million cattle across 30 abattoirs | Annual loss due to fasciolosis at USD 26,000,200,000 (37,678,096,489,282.00 Nigerian Naira) |

| Alhaji & Isola | 2018 | North-Central | Cross sectional | 384 pastoral households | Annual economic impact was estimated at USD 908,463.90 (1,392,413,264.00 Nigerian Naira) |

| Sadiq & Mohammed | 2017 | North-Central | Retrospective | 6 farms across 6 LGA | Cumulative losses (13,000,000 Nigerian Naira)ND, IBD (5,000,000 Nigerian Naira) and AI (2,000,000 Nigerian Naira) |

| Adedeji et al. | 2017 | North-Central | Case study | 231 cattle | Direct economic losses were estimated to be USD 17,377.05 (3,180,000 Nigerian Naira) |

| Alhaji and Babalobi | 2017 | North-Central | Cross sectional | 125 pastoral cattle herds | The total economic cost of CBPP to pastoralists was estimated to be USD 294,800.3 (433,822,225.47 Nigerian Naira) |

| Bello et al. | 2023 | North-Central | Cross sectional | 120 rabbit farmers | Economic losses of USD 250.88 (383,600 Nigerian Naira) |

| Ol-Fadunsin et al. | 2020 | North-Central | Retrospective | 64,125 sheep and 148,887 goats | USD 2,118.61 (339,950 Nigerian Naira) and USD 3,480.31 (558,450 Nigerian Naira) was lost due to the condemnation of the viscera of sheep and goats, respectively. |

| Babalobi et al. | 2007 | South-West | Retrospective | 306 farms | USD 941,491.67 (113, 939,000 Nigerian Naira), Average mortality loss/farm was USD 3076.77 |

| Liba et al. | 2017 | North-East | Cross sectional | 300 livers each of cattle, sheep and goats | An overall economic loss of USD 1,882.50 (602,400.00 Nigerian Naira) per annum due to 753 kg of condemned liver |

| Dakul et al. | 2024 | North-West | Cross sectional | 99 respondents | About 164,755.09 Nigerian Naira loss |

| Nwankwo et al. | 2019 | South-East | Cross sectional | 474 cattle examined | The economic loss due to the condemnation of affected organs was estimated at USD 4,769 (1, 716,900.00) |

| Francisare et al. | 2015 | North-Central | Retrospective | 64,978 slaughtered cattle | A total of 12660 kg of liver was condemned valued at USD 79251.60 (12,660,000.00 Nigerian Naira) |

| Akpabio | 2014 | South-South | Cross sectional | 22,259 slaughtered animals | The overall financial loss was estimated at USD 1683.09 (269,295 Nigerian Naira) accruing from a total of 635.2 kg of liver condemned. |

| Odeniran et al. | 2021 | Did not Specify | Questionnaire, modelling | 527 respondents | Annual estimated losses to AAT in cattle, sheep, goats & pigs were valued at USD 577,700,000 (850,131,766,000.00 Nigerian Naira) |

| Adelakun et al. | 2019 | South-West | Cross sectional | 408 cattle | USD 2,023,076.40 (703,980,070 Nigerian Naira) (EUR 1,725,441.4) |

| Oluwasile et al.Moru et alOladele-Bukola & Odetokun Ogbaje et al | 2020 2018 2014 2025 | South-West North-West North-Central North-Central | Cross sectional Monte-Carlo simulation modelling Retrospective Cross sectional | 52,273 cattle 446 lactations from 155 cows 640,095 cattle 1,654 slaughtered cattle | USD 7,367 (1,200,000 Nigerian Naira) USD 15.87 (5,005.85 Nigerian Naira)The economic impact of the losses due to fasciolosis was estimated at USD 147, 121 (19,618,639 Nigerian Naira) Economic losses due to liver damage were estimated at USD 2,409.12 (1, 050,000 Nigerian Naira) |

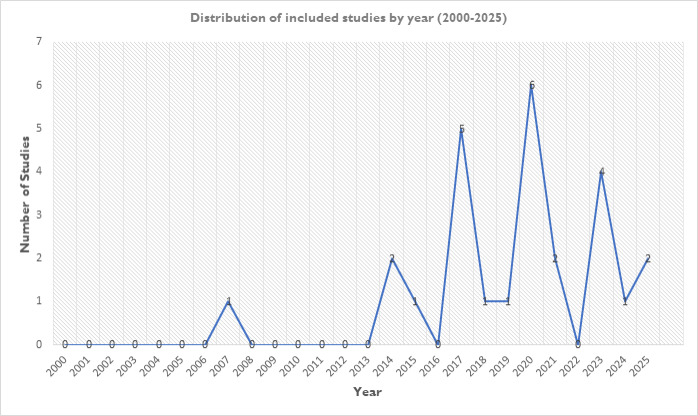

Table I summarises the characteristics and key economic findings of studies assessing the financial impact of major livestock diseases across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones. The included studies span from 2007 to 2025 and vary in design, including cross-sectional, retrospective, and modeling approaches.

*The disparity in the Naira value is due to the different exchange rates at the time of publication for reports not capturing Naira equivalent of financial loss. Subsequently, the currency value was converted to Nigerian Naira equivalent, using current exchange rate.

Figure 2. Included studies ranging from 2007 to 2025, showing a notable upward trend in later years. After a long period of minimal publications (2008–2016), there was a surge in 2017 (5 studies) and a peak in 2020 (6 studies). Subsequent years remained active, with 3 studies in 2023 and 1 each in 2024 and 2025.

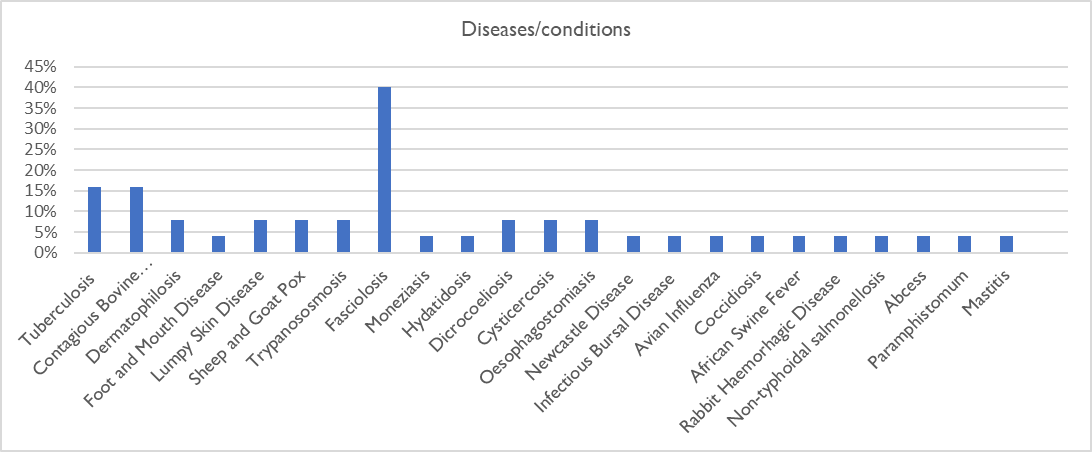

Figure 3. Presents the most prevalent diseases with fasciolosis (helminth infection) being the most frequently diagnosed in abattoirs and responsible for meat condemnation. Fasciolosis is closely followed by bacterial diseases of huge economic importance, including tuberculosis and CBPP, with mastitis among the less frequently reported conditions.

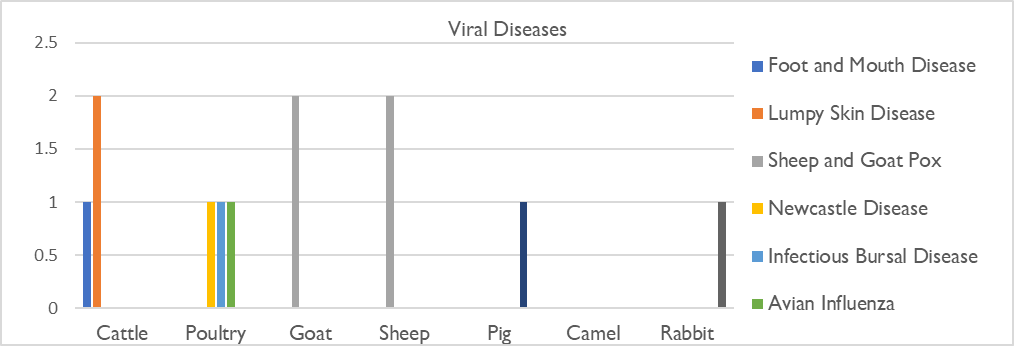

Figure 4. The chart illustrates various viral diseases affecting livestock, with Lumpy Skin Disease, and Sheep & Goat Pox as the most prevalent.

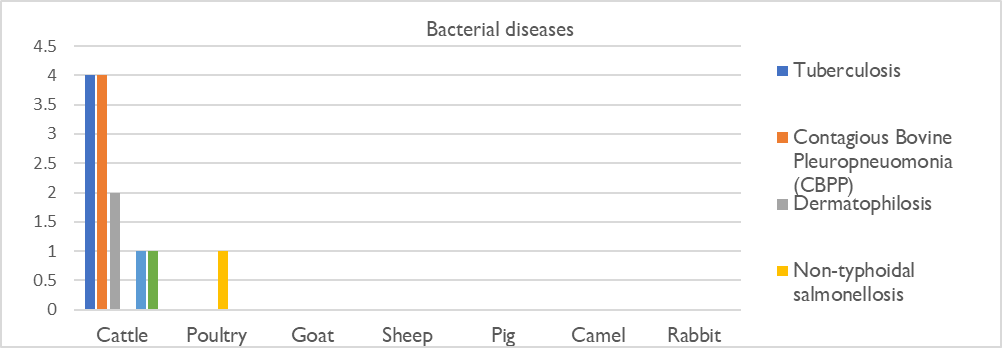

Figure 5. The chart portrays different bacterial diseases affecting diverse livestock, with Tuberculosis and CBPP in cattle being the most prevalent.

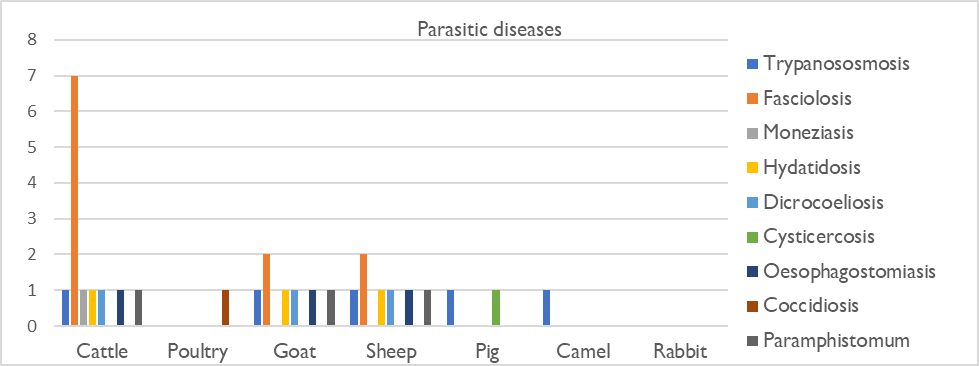

Figure 6. The chart illustrates different parasitic diseases affecting livestock, with Fasciolosis in cattle being the most prevalent.

Table 2. Disease distribution and economic impact based on viral infectious agents

| Disease | Infectious agent | Economic impact |

| Lumpy Skin Disease, Sheep and Goat Pox | Capripoxvirus | USD 32,594,357.05 (49,397,834,776.60 Nigerian Naira) |

| Foot and mouth disease (FMD) | Apthovirus | USD 16,055,368.00 (24,548,818,225.68 Nigerian Naira) |

| Newcastle Disease | Newcastle Disease Virus | USD 8,502.23 (13,000,000 Nigerian Naira) |

| Infectious Bursal Disease | Infectious Bursal Disease Virus | USD 3,270.09 (5, 000,000 Nigerian Naira) |

| Avian Influenza | Type A Orthomyxoviruses | USD 1,308.04 (2,000,000 Nigerian Naira) |

| African Swine Fever | African Swine Fever Virus | USD 941,491.67 (113, 939,000 Nigerian Naira) |

| Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease | Lagovirus | USD 250.88 (383,600 Nigerian Naira) |

| Total: USD 48,450,288.49 (74,809,756,02.30 Nigerian Naira) |

Table 2 presents the distribution and estimated economic losses associated with major viral diseases affecting livestock in Nigeria. Capripoxvirus infections accounted for the highest loss, while rabbit haemorrhagic disease recorded the lowest loss.

Table 3. Disease distribution and economic impact based on bacterial infectious agents

| Disease | Infectious agent | Economic impact |

| Bovine Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium | USD 2,030,590.4 (705,319,720 Nigerian Naira) |

| CBPP | Mycoplasma | USD 2,802.50 (NGN 2,662,375 Nigerian Naira) |

| Dermatophilosis | Dermatophilus | USD 908,463.90 (1,392,413,264.00 Nigerian Naira) |

| Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Mastitis | SalmonellaStreptococcus, Klebsiella, Staphylococcus | USD 224,236,769 (344,703,488,409.87 Nigerian Naira) USD 15.87 (5,005.85 Nigerian Naira) |

| Total: USD 227,178,641.67 (346,803,888,774.85 Nigerian Naira) |

Table 3 presents the economic burden of bacterial diseases in Nigerian livestock. Non-typhoidal Salmonella accounted for the highest loss.

Table 4: Disease distribution and economic impact based on Parasites infectious agents

| Disease | Infectious Agent | Economic Impact |

| Helminth infection | Fasciola, Monezia, Echinococcus, Dicrocoelium, Taenia, Oesophagostomum, Paramphistomum | Total economic impact of condemned visceral organs

USD 781,879.05 (1,060,977,067 Nigerian Naira) |

| African Animal Trypanosomosis | Trypanosoma | Annual estimated losses to AAT in cattle, sheep, goats & pigs USD 577,700,000 (883,395.73 Nigerian Naira) |

| Coccidiosis | Emeria | EUR 58,670,000 (USD 78,905,283.59) (120,872,712,522.09 Nigerian Naira) |

| Total: USD 80,236,789.05 (122,895,746,413.00

Nigerian Naira) |

Table 4 summarizes the economic impact of parasitic diseases in Nigerian livestock. Eimeria infections (coccidiosis) caused the highest estimated loss, followed by Fasciola and other helminths.

4.0 Discussion

This review comprehensively synthesised data on the economic impacts of viral, bacterial, and parasitic diseases on the livestock sector and the Nigerian economy. The review covered the whole of Nigeria, with all six geopolitical zones represented. Although the review covered animal diseases in general, only livestock diseases were considered. The review included viral, bacterial, and parasitic animal diseases. The most prevalent viral disease was sheep and goat pox (9.1%), while contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (18.2%) and fasciolosis (36.4 %) were the most prevalent bacterial and parasitic diseases respectively, reported. Various study designs were employed, with the cross-sectional study being the most reported. Among the reviewed diseases, viral infections accounted for approximately 52% of reported financial losses, followed by parasitic (32%) and bacterial (16%) diseases, highlighting the disproportionate economic impact of viral epizootics. The economic impact of these animal diseases ranged from as low as USD 15.87 (5,005.85 Nigerian Naira) to as high as USD 456,905,311.00 (700,304,123,857.00 Nigerian Naira), which represents a significant economic burden to the Nigerian livestock industry.

Interpretation by thematic category

Viral livestock diseases Viral diseases like foot and mouth disease (FMD), which in terms of economic impact, is considered the most important livestock disease in the world, continue to ravage the Nigerian livestock sector, especially the local pastoral dairy industry (Alhaji et al., 2020). Although mortality is very low, the impact of FMD remains colossal, due to the large number of animals affected. This impact is classified into: (1) direct losses due to reduced productivity and changes in herd structure; and (2) indirect losses attributed to disease control costs (Knight-Jones and Rushton, 2013). In this review, FMD presented the highest economic impact among all the viral diseases, with an estimated economic loss to the tune of USD 16,055,368.00. Approximately 97.1% of this total economic cost was attributed to morbidity and mortality, while only 2.9% was attributable to control costs. This demonstrates the significant economic impact of FMD on the Nigerian economy (Alhaji et al., 2020). Nigeria’s impact represents about 0.08%-0.25% of the global impact. Although FMD is vaccine-preventable, farmers often refrain from vaccinating their animals, and in cases of outbreaks, they resort to local management of the disease. Some farmers are also unaware that FMD vaccines exist. Sheep and goat pox (SGP) caused by Capripoxvirus, had a greater economic impact on transhumance than sedentary herds, most likely due to differences in management systems and disease exposure patterns. Furthermore, depending on the approach and government subsidy levels taken into consideration, vaccination is an economically feasible control method both at the herd and regional levels (Rawlings et al., 2022). Outbreaks of African Swine Fever (ASF) severely impact Nigeria’s livestock industry, resulting in significant loss of livelihoods (Oluwaseun et al., 2023).

Bacterial diseases Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP), Tuberculosis, and Dermatophilosis, alongside other bacterial diseases, have caused the Nigerian livestock sector severe economic losses. Clinical dermatophilosis had an estimated annual economic impact of USD 908,463.9 (Alhaji and Isola 2018). In Nigeria, dermatophilosis cases are increasingly reported to veterinary clinics and teaching hospitals. This could be attributed to the increase in crossbreeding between indigenous cattle and exotic breeds. Temperate breeds have been demonstrated to be more susceptible to dermatophilosis (Babashani, 2017). Huge losses are incurred from this chronic disease due to the protracted treatment course. Furthermore, dermatophilosis produces damaging lesions on hides, which severely affect market valuation. Ruminants are further threatened by tuberculosis, a contagious and economically devastating disease, with an estimated direct and indirect economic impact of USD 2,030,590.4 (705,319,720 Nigerian Naira), resulting from the loss of the animal or through condemnation of affected organs. Due to the chronic nature of tuberculosis, huge losses are incurred from its treatment costs and reduced animal productivity. Tuberculosis also has the potential to infect humans, thereby making Nigerian pastoral farmers prone to the disease due to their practice of consuming unpasteurized milk, often reducing their quality-adjusted life years. Nigeria’s poultry industry is also impacted by pathogens, such as Salmonella, with an estimated direct animal loss value of USD 224,236,769 (344,703,488,409.87 Nigerian Naira) in 2020. In the same year, the poultry sector contributed about 6-8% of real GDP and approximately 25% Nigerian agricultural GDP which makes these losses more concerning (Sanni et al., 2023).

Parasitic diseases Parasites remain a burden to the well-being of livestock, impacting their productivity and causing huge financial losses to the economy of many nations (Ola-Fadunsin et al.,2020). This review estimated a cumulative loss of USD 79,454,910.00 (121,834,769,346.00 Nigerian Naira). This represents the second-highest cumulative impact after viral estimates. Fasciolosis remains the most prevalent parasitic condition leading to many visceral organ condemnations, especially infested livers in Nigerian abattoirs (Ola-Fadunsin et al., 2020). Poultry production is crucial for food and nutrition security level of many nations, through the provision of eggs and meat, as well as income generation. However, diseases such as coccidiosis are among the major constraints to the poultry industry in Nigeria as they severely affect the health, welfare, and production performance of chickens (Midala et al.,2025).

Comparison with previous studies A comparable economic burden has been reported in Ethiopia where FMD remains widespread and economically devastating, with losses largely driven by reduced milk production, reproductive impairment, and restrictions on market access and export opportunities, resulting in estimated monetary losses of approximately USD 14,000,000 (Zewdie et al., 2023). Similarly, CBPP continues to exert a significant economic impact across Africa, including Ethiopia, through a combination of direct production losses, cattle mortality, and substantial expenditure on disease control. In Ethiopia, national costs associated with CBPP control, particularly vaccination and disease management, have been estimated at over USD 2,347,400, indicating the financial burden placed on both governments and livestock owners (Tambi et al., 2006). Parasitic diseases also contribute largely to livestock-related economic losses, as shown by coccidiosis in Ethiopia’s poultry sector, where mortality, reduced growth performance, diminished egg production, and recurrent costs of coccidiostat use collectively impose a substantial aggregate economic burden, particularly in the context of the country’s large poultry population (Habtamu and Gebre, 2019).

Policy and management implications The impact of animal diseases extends beyond direct production losses. These diseases disrupt market access, especially in developing countries seeking to participate in international trade. For example, the presence of FMD in endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa restricts cattle trade for beef (Countryman et al., 2024). This has significant economic implications for many developing countries, including Nigeria. In addition, although in Nigeria, the translocation of animals is a necessary act because sometimes animals may need to be relocated to other areas for a number of reasons, including feeding as seen in nomadism and transhuman, during droughts, marketing for slaughter, and breeding. Such movements, although necessary, usually come at a cost, which has been blamed by researchers for propagating infections. This invariably translates to losses in production output. Addressing the economic challenges requires a multidimensional approach involving policymakers, researchers, and farmers. A combination of strategies, including surveillance, vaccination, enhanced biosecurity, increased farmer sensitisation. In addition, veterinary and agricultural institutions should be supported to enhance farmers’ access to timely information. This approach should encompass free or subsidized animal vaccination campaigns and periodic educational initiatives to elucidate optimal animal health practices. Rural access to veterinary services should be improved. Additionally, investment in innovative diagnostic technology and disease surveillance infrastructure to enhance early disease detection, diagnosis, and reporting capacity. Moreover, comparative analyses of disease management strategies across various countries may yield valuable insights into effective control methodologies.

Future research directions Computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, which have increasingly become important tools for estimating the economy-wide impacts of animal diseases, should be employed for the most prevalent livestock diseases in Nigeria. These models will capture the complex interactions between different sectors of the economy, providing a more comprehensive view of disease impacts than partial equilibrium models. This model has produced promising results in assessing the impacts of the 2001 FMD outbreak in the United Kingdom, simulating a 0.8% decrease in gross domestic product (GDP), amounting to approximately EUR 10,000,000,000, (Bose and Kumar, 2025).

Data limitations: Inconsistency in data availability across different regions of the country, especially in the Northwest, South-South, and South-East regions of the country, was a major limitation that needs to be taken into consideration in interpreting this review.

Methodological variability: Economic evaluation methods employed were not uniform, with variations in cost estimation models and currency, limiting the generalizability of our findings.

Analytical constraints: The depth of the economic analysis was limited by the absence of detailed data distinguishing between direct and indirect economic losses.

Geographical imbalance: Most of the available data were regional, often not capturing the entire country’s disease(s) impact.

Future research needs: There is a need to obtain robust data on the overall country estimates for endemic livestock disease(s), capturing both visible and invisible losses, using economic models, to enable the generalisation of research findings.

5.0 Conclusion

Animal diseases cause economic losses worldwide. The impact is more pronounced in developing countries like Nigeria, where livestock remains a major contributor to Nigeria’s GDP and rural employment. This review found that viral, bacterial, and parasitic diseases cause substantial financial losses to the Nigerian livestock sector. Across 27 reviewed studies, economic losses from animal diseases ranged from USD 15 to USD 456 million, with viral diseases contributing the largest share. These impacts occur through reduced productivity, increased mortality, and disruptions in domestic and export markets, emphasising the need for improved data and economic modelling. In addition, these diseases further threaten Nigeria’s food security in the face of a growing population. Targeted investments in disease surveillance, farmer education, and vaccination programmes are essential to reduce losses and strengthen national food security. There is a need to obtain robust data on the overall country estimates for endemic livestock disease(s), capturing both visible and invisible losses, using economic models, to enable the generalisation of research findings

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation: Aliyu Abdulkadir, Abubakar Y Hassan; Methodology: Abubakar Y Hassan, Ammar U Bashir, Ishaq Ibrahim; Resources: Mustapha K Moyi, Ishaq Ibrahim, Yero I Hassan; Writing – Original draft preparation: Abubakar Y Hassan, Ammar U Bashir, Ishaq Ibrahim, Mustapha K Moyi, Bilkisu A Ibrahim, Muhammed S Isah, Maryam Nasiru; Writing – Review and editing: Abubakar Y Hassan, Aliyu Abdulkadir, Ammar U Bashir, Muhammed S Isah, Ishaq Ibrahim, Ibrahim, Yero I Hassan, Mustapha K Moyi, Bilkisu A Ibrahim, Maryam Nasiru; Supervision: Aliyu Abdulkadir, Abubakar Y Hassan. All authors have read and agreed to this revised version of the manuscript.Funding: This research received no external funding.

Ethics Approval Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Acknowledgments: The authors gratefully acknowledge the Departments of Veterinary Medicine, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, and the National Animal Production Research Institute at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and the Sokoto State Ministry of Livestock & Fisheries Development.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Artificial Intelligence: AI was not used for this review.

References

Adedeji A, Adole J, Dogonyaro B, Kujul N, Tekki I, Asala O, Chima N, Dyek D, Maguda A. 2017. Recurrent outbreaks of lumpy skin disease and its economic impact on a dairy farm in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Nigerian Veterinary Journal, 38, 151-158. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/nvj/article/view/164121

Adelakun OD, Akinseye VO, Adesokan HK, Cadmus SIB. 2019. Prevalence and economic losses due to bovine tuberculosis in cattle slaughtered at Bodija municipal abattoir, Ibadan, Nigeria. Folia Veterinaria, 63(1), 41—47. https://doi.org/10.2478/fv-2019-0006

Alhaji NB, Amin J, Aliyu MB, Mohammad B, Babalobi OO, Wungak Y, Odetokun IA. 2020. Economic impact assessment of foot-and-mouth disease burden and control in pastoral local dairy cattle production systems in Northern Nigeria: A cross-sectional survey. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 177, 104974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.104974

Alhaji NB, Babalobi OO. 2017. Economic impacts assessment of pleuropneumonia burden and control in pastoral cattle herds of North-Central Nigeria. Bulletin of Animal Health and Production in Africa, 65(2), 235-248. https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S180025

Alhaji NB, Isola TO. 2018. Pastoralists’ knowledge and practices towards clinical bovine dermatophilosis in cattle herds of North-Central Nigeria: the associated factors, burden and economic impact. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 50, 381-391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-1445-y

Akpabio U. 2014. Incidence of bovine fasciolosis and its economic implications at Trans-Amadi abattoir, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. 5(3), 206-209. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.apg.2014.5.3.85139

Babalobi OO, Olugasa BO, Oluwayelu DO, Ijagbone IF, Ayoade GO, Agbede SA. 2007. Analysis and evaluation of mortality losses of the 2001 African swine fever outbreak in Ibadan, Nigeria. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 39(7), 533-542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-007-9038-9

Babashani M. 2017. Prevalence and production impacts of Dermatophilosis in cattle. Proceedings of the 54th Annual Congress of the Nigerian Veterinary Medical Association, Kano, Nigeria. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shuaib-Adamu/publication/328430399_Book_of_Proceeding_Kano_2017/links/5bcdf7974585152b144da5da/Book-of-Proceeding-Kano-2017.pdf

Bello MA, Ayeni MD, Adewumi MO, Ahmed IA. 2023. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease outbreak in Nigeria and its economic impacts on rabbit farmers in Kwara State. Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Tarım Bilimleri Dergisi, 28(2), 467-476. https://doi.org/10.37908/mkutbd.1248852

Blake DP, Knox J, Dehaeck B, Huntington B, Rathinam T, Ravipati V, Ayoade S, Gilbert W, Adebambo AO, Jatau ID, Raman M, Parker D, Rushton J, Tomley FM. 2020. Re-calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens. Veterinary Research, 51(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-020-00837-2

Bolajoko MB, Van Gool F, Peters AR. 2020. Field survey of major infectious and reproductive diseases responsible for mortality and productivity losses of ruminants amongst Nigerian Fulani pastoralists. Gates Open Research, 4, 162. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13164.1

Bose B, Kumar SS. 2025. Economic burden of zoonotic and infectious diseases on livestock farmers: a narrative review. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 44, 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-025-00913-3

Countryman AM, de Menezes TC, Pendell DL, Rushton J, Marsh TL. 2024. Economic effects of livestock disease burden in Ethiopia: A computable general equilibrium analysis. PLoS ONE, 19(12), e0310268. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0310268

Dakul DA, Samaila AB, Abongaby GC, Ogbole E, Salami O, Eluma M, Mamman SA. 2024. Economic impact of trypanosomosis on camels (Camelus dromedarius) in North-West, Nigeria. African Journal of Agriculture and Food Science, 7(3), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.52589/ajafs-2bbzmwhd

Dauda ID, Binhambali A, Jibril AH, Idris ZO, Akorede FR. 2025. Economic impact of fetal wastage and common diseases, along with their incidence rates and seasonal variations, at an abattoir in FCT, Nigeria. PLoS ONE, 20(2), e0310806. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0310806

FAO. 2012. Lessons learned from the eradication of rinderpest for controlling other transboundary animal diseases. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/4/i3042e/i3042e.pdf

FAO. 2020. Nigeria livestock roadmap: Policy framework. FAOLEX. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig228496.pdf

Francis E, Thlama P, Lawan FA, Lawal J, Ejeh SA, Hambali IU. 2015. Seasonal prevalence of bovine fasciolosis and its direct economic losses due to liver condemnation at Makurdi abattoirs, North Central Nigeria. Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.4314/sokjvs.v13i2.7

Habtamu Y, Gebre T. 2019. Poultry coccidiosis and its economic impact: A review article. British Poultry Science, 8(3), 76-88. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.bjps.2019.76.88

Kappes A, Tozooneyi T, Shakil G, Railey AF, McIntyre KM, Mayberry DE, Rushton J, Pendell DL, Marsh TL. 2023. Livestock health and disease economics: a scoping review of selected literature. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 10, 1168649. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1168649

Knight‐Jones TDJ, Rushton J. 2013. The economic impacts of foot and mouth disease – what are they, how big are they and where do they occur? Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 112, 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.07.013

Liba JW, Atsanda NN, Francis MI. 2017. Economic loss from liver condemnation due to fasciolosis in slaughtered ruminants in Maiduguri abattoir, Borno State, Nigeria. Journal of Advanced Veterinary and Animal Research, 4(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.5455/javar.2017.d192

Limon G, Gamawa AA, Ahmed AI, Lyons NA, Beard PM. 2020. Epidemiological characteristics and economic impact of lumpy skin disease, sheep pox and goat pox among subsistence farmers in Northeast Nigeria. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00008

Lewis RA, Kashongwe OB. Bebe BO. 2023. Quantifying production losses associated with foot and mouth disease outbreaks on large-scale dairy farms in Rift valley, Kenya. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 55(5), 293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-023-03707-z

Midala, C.A., Kyari, F., Thekisoe, O. et al. Parasites of poultry in Nigeria from 1980 to 2022: a review. (2025). Journal of Parasitic Diseases, 49, 523–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-025-01792-5

Moru, N., Umoh, J., Maikai, B., Barje, P., & Amuta, P. 2018. Milk yield losses and cost of clinical mastitis in Friesian × Bunaji crossbred dairy cows in Zaria, Nigeria. Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, 16(2), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.4314/sokjvs.v16i2.4

Natsa RT. 2025. FG targets $74bn from livestock investments. Business Day. https://businessday.ng/news/article/fg-targets-74bn-from-livestock-investments/

National Bureau of Statistics. 2024. Nigerian Gross Domestic Product Report Q1 2024, Issue 41. http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng

National Bureau of Statistics. 2025. Agricultural sector employment in total employment in Nigeria from 1991 to 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1288871/agriculture-sector-share-in-employment-in-nigeria/

Njoga EO, Ilo SU, Nwobi OC, Onwumere-Idolor OS, Ajibo FE, Okoli CE, Jaja IF, Oguttu JW. 2023. Pre-slaughter, slaughter and post-slaughter practices of slaughterhouse workers in Southeast Nigeria: Animal welfare, meat quality, food safety and public health implications. PLoS ONE, 18(3), e0282418. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282418

Nwankwo I, Onunkwo I. 2019. Postmortem prevalence of fasciolosis and contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP) and economic losses in cattle at Nsukka abattoir, Nigeria. Veterinary World, 16, 3418–3426. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2019.3418-3426

Odeniran PO, Omolabi KF, Ademola IO. 2020. Economic model of bovine fasciolosis in Nigeria: an update. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 52(6), 3359–3363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02348-w

Odeniran PO, Onifade AA, Omolabi KF, Ademola IO. 2021. Financial losses estimation of African animal trypanosomosis in Nigeria: field reality-based model. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 53, 411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-021-02603-8

Ogbaje, L. J., Malann, Y. D., 1Azare, B. A., Njoku, M., and Jegede, O. C. 2025. Economic impact of high burden of fascioliasis in FCT, caused by damage to liver. Direct Research Journal of Agriculture and Food Science, 13(2), 37-41. https://journals.directresearchpublisher.org/index.php/drjafs/article/view/11

Ola-Fadunsin SD, Uwabujo PI, Halleed IN, Richards B. 2020. Prevalence and financial loss estimation of parasitic diseases detected in slaughtered cattle in Kwara State, North-central Nigeria. Journal of Parasitic Diseases, 44, 740–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-019-01154-y

Odetokun, Ismail & Oladele-Bukola, M.O. 2014. Prevalence of bovine fasciolosis at the Ibadan Municipal Abattoir, Nigeria. African Journal of

Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 14(4), 9055-9070. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.64.11720

Awosile BB, Awoyomi OJ, Kehinde OO. 2020. Prevalence and economic loss of bovine tuberculosis in a municipal abattoir, Abeokuta Southwestern Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Animal Production, 40(2), 216–223. https://doi.org/10.51791/njap.v40i2.1229

Oluwaseun A. Ogundijo, Oladipo O. Omotosho, Ahmad I. Al-Mustapha, John O. Abiola, Emmanuel J. Awosanya, Adesoji Odukoya, Samuel Owoicho, Muftau Oyewo, Ahmed Ibrahim, Terese G. Orum, Magdalene B. Nanven, Muhammad B. Bolajoko, Pam Luka, Olanike K. Adeyemo. 2023. A multi-state survey of farm-level preparedness towards African swine fever outbreak in Nigeria, Acta Tropica, 246, 106989, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2023.106989

Rawlins ME, Limon G, Adedeji AJ, Ijoma SI, Atai RB, Adole JA, Dogonyaro BB, Joel AY, Beard PM, Alarcon P. 2022. Financial impact of sheep pox and goat pox and estimated profitability of vaccination for subsistence farmers in selected northern states of Nigeria. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 198, 105503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2021.105503

Rich KM, Perry BD. 2011. The economic and poverty impacts of animal diseases in developing countries: new roles, new demands for economics and epidemiology. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 101(3–4), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.08.002

Sadiq M, Mohammed B. 2017. The economic impact of some important viral diseases affecting the poultry industry in Abuja, Nigeria. Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, 15(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.4314/sokjvs.v15i1.2

Sanni AO, Onyango J, Rota AF, Mikecz O, Usman A, Pica-Ciamarra U, Fasina FO. 2023. Underestimated economic and social burdens of non-Typhoidal Salmonella infections: The One Health perspective from Nigeria. One Health, 16, 100546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100546

Sertoglu K, Sevin U, Bekun FV. 2017. The contribution of the agricultural sector on economic growth of Nigeria. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(2), 547–552. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/article/view/4088

Sowunmi, F. 2025. Poultry Farmers’ Resilience to the Outbreaks of Disease in Oyo State, Nigeria. Agricultural Research & Technology: Open Access Journal, 29(2), 556441. https://doi.org/10.19080/ARTOAJ.2025.29.556441

Tawfik GM, Dila KAS, Mohamed MYF, Tam DNH, Kien ND, Ahmed AM, Huy NT. 2019. A step-by-step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Tropical Medicine and Health, 47, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6

Zewdie G, Akalu M, Tolossa W, Belay H, Deresse G, Zekarias M, Tesfaye Y. 2023. A review of foot-and-mouth disease in Ethiopia: Epidemiological aspects, economic implications, and control strategies. Virology Journal, 20, 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-023-02263-0

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, institutional affiliations, data contained in all publications, and all responsibilities for accuracy are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MARCIAS AUSTRALIA and AJAVAS/or the Editor(s). MARCIAS AUSTRALIA and AJAVAS/or the Editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.